Over my decades-long history as both a blogger, author, and public speaker (as well as being a Ph.D. in Psychology who sees clients), I have come to appreciate the power of words. I often hear someone say that “it’s just a semantic difference” when discussing the use of different words that are seen as having the same meaning. Yet, I have found that the differences between words are usually much more than semantic.

Words are so important because they act as a powerful lens through which we perceive, interpret, and analyze our world. Words also label and define our experiences; what we think, the emotions we feel, the actions we take, and the interactions we have with others. As a result, when speaking or writing, it’s essential to use words that are highly descriptive of what we want to communicate.

With this context established, let me introduce you to two very important words in our “I’m a human being” lexicon: react and respond. Your first thought may be: “What’s the difference between react and respond? Don’t they mean the same thing?” At first blush, they do seem have the same meaning. In fact, my thesaurus indicates that each is a synonym for the other. Yet, through my client work, writing, and public speaking I have come to see a profound difference in the meaning of these two words, particularly when people are faced with difficult situations. I have observed that each of these words produce very different, well, reactions/responses to life experiences, particularly stressful ones.

Here’s a question for you: Would you rather “react” or “respond” to a situation? Before you answer, let me explain the difference. The Latin root of react is” “back + to do, perform.” The key takeaway here is that you are taking action back at someone or something. In contrast, the Latin root of respond is “back + answer.” The key takeaway here is that you are answering back to someone or something, usually in words.

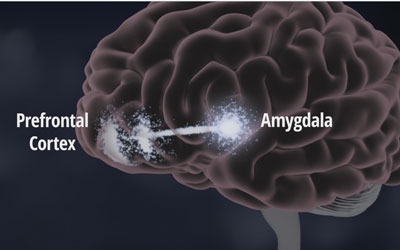

Humans are wired through millions of years of evolution to react in certain ways to situations that present themselves in our lives. This focus on reaction is grounded in our survival instinct and the understanding that, on the Serengeti 250,000 years ago when we officially became homo sapiens, there was no time to ponder and deliberate before taking action because during that time, our ancestors would likely be killed. We were still guided predominantly by our amygdala and our emerging cerebral cortex had little need to be engaged. Our amygdala perceived a threat to our survival and triggered our fight-or-flight reaction (not response!) which increased our chances of living another day, passing on our genes, and propagating our species.

These same instinctive and visceral reactions arise when confronted by modern-day situations in which our physical survival isn’t threatened (not too many saber-toothed tigers or hostile tribes in America these days), but rather by what I call “psychological” survival which involves threats to our self-identity (e.g., how we describe ourselves), self-esteem (e.g., how we evaluate ourselves), and our goals (e.g., educational, career, and financial aspirations). Present-day survival “instincts,” what we would commonly refer to as our “baggage,” include perfectionism, fear of failure, need for control, need to please, among other strategies that protect our psychological survival.

As we often learn the hard way, what worked on the Serengeti so long ago doesn’t work in most situations in the 21st century. Experiences we were faced with then hold little resemblance to those we face now. Herein lies the important distinction in how these two words are used and, in turn, impact us.

Due to the complexities of life today, reacting based on our primitive instincts or baggage rarely leads to positive outcomes. For example, if a colleague gets a promotion that you had expected to get, you will naturally react with disappointment, hurt, and potentially anger. You might let that anger overwhelm you resulting in your storming into your boss’s office and threatening him or her, a reaction that I’m sure you agree would not be helpful to your survival, whether physical or psychological.

Thankfully, a part of our evolution has involved the emergence of the cerebral cortex and, more specifically, our pre-frontal cortex which governs what has become widely known as our “executive functioning” (though I have known executives who rarely use this function!) which is associated with memory, analysis, planning, problem solving, weighing risks and rewards, considering short-term and long-term costs and benefits, and decision making. Referring back to the Latin root of respond, in answering in words, we are activating our cerebral cortex and thus using our evolved brain to deal with the complicated, and far more common, challenges we face in the 21st century. We are able to engage in deliberate thinking and thoughtful decision making which then guide our thinking, emotions, and behavioral responses (there’s that word again!) to the situation with which we are faced. Clearly, these responses produce much more desirable outcomes to those in which we simply react.

Even though our amygdala may have outlived most of its usefulness (but will likely not be replaced by our cerebral cortex as the first stop on the information highway into our brains for several more eons of evolution), it still exerts undue influence over our thinking, emotions, and behavior. Yet, thanks to our pre-frontal cortex, we humans do have the capacity to override it in many situations including stressful ones. But it takes preplanning (a strength of the prefrontal cortex), awareness, determination, and time for our evolved brain to override our primitive brain and better serve our interests and goals in the complex world in which we live. So, the next time you are confronted with the modern-day equivalent of your survival being threatened, how can you be sure that you will respond rather than react? Here are four practical steps you can take.

First, you can catalog the common situations in which your amygdala is activated leading to a reaction on your part. This knowledge acts to alert your pre-frontal cortex that a reaction is imminent when these circumstances arise, thus preparing you to intervene and stop the reaction before it occurs.

Next, this preparation enables you to quickly recognize such a situation when faced with one. This simple of act of detection means that your pre-frontal cortex is activated and already suppressing your amygdala’s urges.

Then, very importantly, stop! By hitting the “pause” button and giving yourself several seconds, you interrupt the information going to your amygdala and prevent it from causing you to react in that moment. In doing so, you also redirect further information from your amygdala to your pre-frontal cortex, allowing the latter to become further activated and take over control of your thinking, emotions, and behavior.

Finally, with your pre-frontal cortex in command, you can then play to its strengths and, based on a careful analysis of the circumstances, make a deliberate decision about how best to respond to the situation in a way that will lead to the best possible outcome.